People do not Become Systems Leaders Without Adequate Tools

by Nathan Senge

Embracing the Leadership Paradox

“I believe that many NGOs seek to truly collaborate amongst multiple stakeholders, but our past experience of collaboration has not been positive. We just aren’t convinced that we can do it; we need to learn how to do it,” says NOS co-founder Alejandro Robles. “This is where the collective systems learning tools we have used come in. Over time, they have gradually given us the confidence and the clarity that we can create the sorts of relationships with peer organizations that are truly needed in order to transform fisheries.”

Beyond the specifics of different particular tools, the NOS story shows how getting started in deep change involves deeper listening to one another and deeper sensing and understanding of the reality of a complex setting. Put differently, real change starts when people combine appropriate tools with the right underlying intention. This intention involves allowing for a generative community building space, and is tantamount to letting go of control and becoming more vulnerable to one another’s views. People then start to discover what they themselves do not see, including how “I” or “we” may be a part of what is keeping them stuck. This spirit of deep personal and collective learning is essential; we have seen many people accomplish very little using the same tools because they lack a genuine commitment to such learning.

For NOS, this path started with check-ins and basic dialogue tools. For others, it could start with other tools like learning-sensing journeys1 or peer shadowing2.

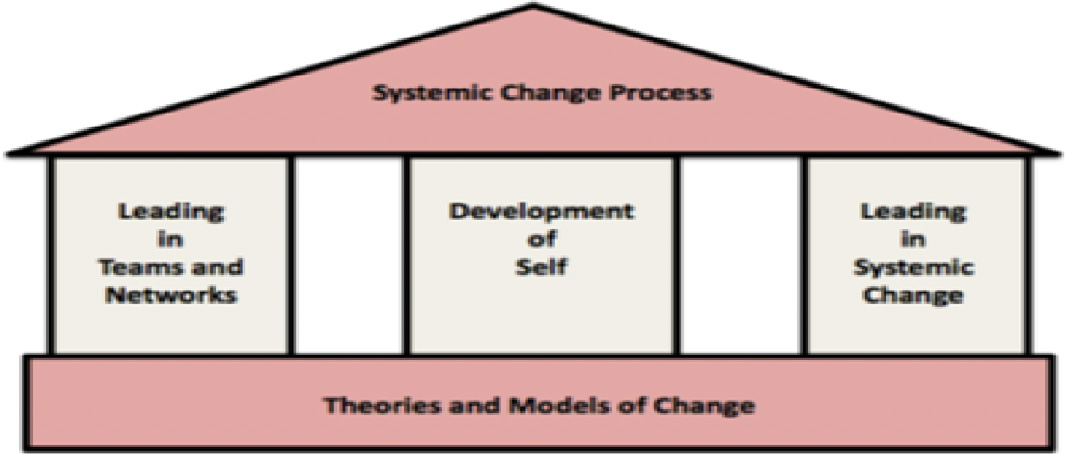

The tools used by NOS and El Manglito in this story are part of a systems change toolkit that has been growing for several decades. One of the aims of the Academy is to make these tools increasingly accessible and usable, and to this end we have grouped the hundreds of tools available into five broad areas:

- Development of Self

- Leading in Teams and Networks

- Leading in Systemic Change

- Theories and Models of Change

- Managing Systemic Change Processes

To this end, a new interactive System Leader’s Fieldbook website has just been released. The links above are to specific tools referenced on this site.

Seeing the systemic forces we co-create and then become stuck in

Fishers stepping back to see the systems they co-create

Starting in 2011-12, Joe Hsueh, who later became a Founding Fellow of the Academy for Systems Change, began co-leading sessions with NOS staff members and Academy for Systems Change fellows Christian Liñán-Rivera and Alejandro Flores to help fishers explore the basic system dynamics they were a part of. The mapping was done as an interactive co-learning process, both in El Manglito and in the Upper Gulf.

Their basic aim was to engage fishing community members in thinking together about the systemic forces they were both operating within and contributing to. For example, the fishers started to see the multiple forces that drive them to overfish, starting with the basic self-reinforcing feedback loop that comes from rising catches and rising incomes, which drives a desire to catch even more. This economic success growth loop can eventually trigger more problematic vicious cycles. For example, “when fishermen bring a higher quantity of fish and flood the market,” says Hsueh, “this lowers the price and makes it hard for local buyers because the margins get too low.” Facing falling margins can “cause fishermen to fish more in order to sustain their incomes, worsening the situation and fostering a mental model of focusing more on quantity [of fish caught] instead of quality.” Herein lies the basic paradox that often drives overfishing, especially in developing country contexts: when incomes rise, fishers fish more, and when incomes then start to fall due to lowering market prices, fishers fish even more still.3 This basic drive to overfish is exacerbated when fish stocks then start to decline, and fishers have to work even harder to catch the increasingly scarce population, thereby effecting an overall tragedy of the commons-based population collapse the fishers call “the race for fish.”

Together, Robles, Liñán-Rivera, Flores, and Hsueh led many systems mapping sessions with fishers to explore how so many fishing communities become ensnared in these dynamics. These dynamics must be understood if fisheries are to change their practices and align their efforts at larger-scale restoration. Recall the three basic reinforcing loops described above :

- rising economic opportunity while fish are plentiful

- sustaining income when prices fall as the market is flooded

- the “race for fish” as the fish population finally declines

Systems maps were used to explore a still broader set of inter-connected dynamics, like erosion of ecological carrying capacity due to habitat damage and pollution, increases in non-fishing activities like agriculture and tourism, limiting overfishing through habitat and pollution conservation, and developing alternative income streams for local residents like eco-tourism. These systems maps also explored how a healthy ecosystem can improve fish quality, leading to higher price options for fishers amidst lower catch quotas (one of the goals of the new fishing cooperative, OPRE), and how civic engagement and stakeholder trust can both drive and benefit from scaling fishery restoration throughout surrounding fisheries.

Systems mapping as a vehicle for reflection

“It is only through reflection that we change our history” – renowned biologist Humberto Maturana

“The real power,” says Hsueh, “comes when people see deeper cycles they are a part of, and realize that it is no accident that they have experienced the difficulties they have been living through. That they themselves were a part of creating those difficulties. When this is done collectively and carefully, people start to see themselves in the systems map, and through the part they play, they sense what’s happening in the larger system. When people are all together in the room, they realize that while from their individual perspective they might be doing rational things, they collectively are caught in a cyclical trap they unwittingly made for themselves. In this case, they were all working harder and harder to earn less income.”

In Hsueh’s words, overfishing is “driven by a lack of trust on all sides. But, ironically, seeing together how this lack of trust punishes everyone can lay a foundation for building trust going forward. When done with real listening and partnership, the systems mapping can be another strategy for re-building that trust.”

When Hsueh and Robles first met at the SoL Executive Champions’ Workshop in August of 2011, Robles said that he “knew little about system mapping. But we had already started to bring some of the learning tools into NOS in 2010. We had started to see the power of slowing down and helping people reflect and connect with one another, and to think in general about deeper sources of problems. It was then a natural next step to see how we could think further about the specific systems structures we were trapped within.”

While Hsueh had participated in many collaborative systems maps, he had never done work in fisheries until Robles and Liñán-Rivera asked him to come to NOS. Once there, he saw the depth of NOS’s commitment. “It’s common today for people to say how important systems thinking is and to be interested in systems mapping, but most do not see the deeper change processes required for real impact.” Combining the systems maps with their work on dialogue and deep conversations, NOS staff members became able to see the mapping as a reflective tool, helping them think together about the true sources of their problems. “Everyone wants to understand systems,” says Hsueh,”but few want to see how they are shaping those systems themselves – I could tell it was different for the NOS staff.”

Over time, “working as a team, we were helping local resident systems thinkers step forward,” says Hsueh. “An important part of systems change work is helping build local capacity of people on the ground to be able to think systemically and work collaboratively with each other. With people like Flores and Liñán-Rivera leading, I knew that gradually local leadership would emerge to take over the work.”

(1) https://www.presencing.com/tools/sensing-journey

(2) https://www.presencing.com/tools/shadowing

(3) Commodity System Challenges, Report of The Sustainability Institute, April, 2003. This report was one of the key organizing documents for the Sustainable Food Lab network.