by Peter Senge

There is no doubt the Mississippi River program is having big impacts within TNC as an organization and its momentum is growing. The program “has taken off,” says Milliken. “The collaboration goal of MsB is a beacon and (has) pointed the way,” says Reuter. The project “is looked at as a place where we’re learning how to do this kind of collaborative work, and it is serving as a source of inspiration for other like-minded projects around TNC.” “This experience has changed me,” says Tabas. “Working in teams has created new expectations. I’m currently using it around green infrastructure initiatives in Detroit.

“There are a lot of others in TNC who view MsB as an exemplar,” Tabas adds. “Today, the big ‘Adjust’ meetings are quite large. People see the value in attending, and the meetings are a way to further embed these new ways of working collaboratively. TNC leadership is watching our progress carefully. Rising players in new projects are rising into new positions and using this approach.”

But with success also comes new challenges.

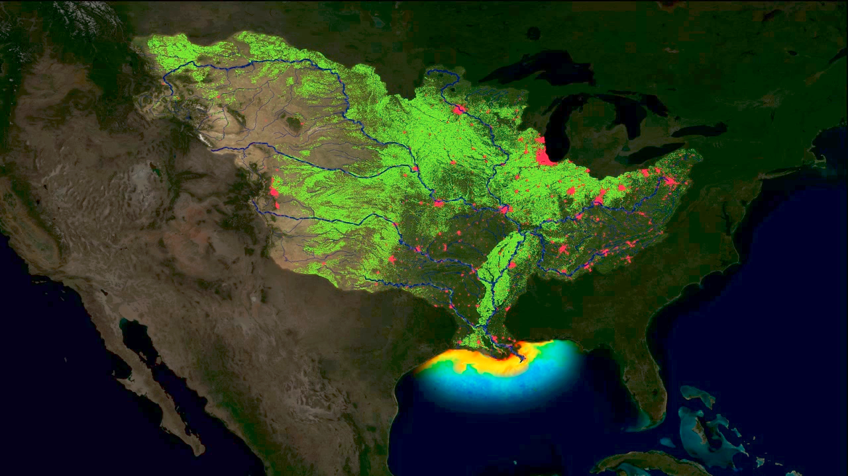

First, there is the matter of managing expectations for the long run against the background of inherent uncertainties and the inevitable rises and falls of emotion. One of the defining features of complex systems are time delays, which also means, on the one hand, you can be on the right track and still not know for many years and, on the other, you need to guard against confusing short-term fortuitous improvements with deeper changes. Clemens points out that the EPA is “about to announce that the dead zone in the Gulf is at one of the smallest levels ever… (but) we don’t want to declare victory yet as many variables can cause changes over time, and nutrient loading in the Upper Mississippi is actually growing.” Reuter points to a recent “sobering” study out of Iowa that’s shows “over the last 10 years, even with all we’ve done, we still see a 45 % increase in N loading. We are not sure why. Climate change does not explain it. Could be lag times. Big answer is probably application rates, especially linked to expanding animal feedlots.” He adds that there are “lots of political issues around this concerning the data coming from Dept. of Ag…. (but) a 20% reduction of dead zone by 2025? Hard to believe we could get there.”

Second, there are the inevitable pressures to “scale up” and speed up after spending so much time learning how to slow down and engage more key players in more authentic dialogue. “The pace of scaling up has increased,” says Glendening. “For instance, in the domain of working with the agriculture supply chain and multi-states retailers, we are employing scientific knowledge more efficiently by shifting key scientists across state boundaries. Fundraising across the basin for the whole system has increased. North American Ag program’s partnership with companies and with the MsB program has also increased. Conversant’s conversation principles have been employed by state chapters who have invested in them… There has been a growing involvement of trustees in this work, particularly in the Midwest.” But, as early as the Tampa meeting in 2016, “The challenge we faced involved trying to get new people to see how we could work together differently – how to ‘on-board’ them?” asked Glendening. Going faster in response to pressures to speed up might create the illusion of movement without shifting underlying mental models – leading ultimately to little deeper or longer lasting change

Part of what is needed is growing a deep appreciation of distributed teams within an organization based in individual expertise and small groups working on well-defined tasks. “I remember using a track meet metaphor,” says Glendening. “What does it take to win as a team—especially when each person has their own event. I had firsthand experience with this from high school and it was profound. I was in a field event, but the whole team could not do well without top results from the track athletes, too.”

Reuter says, “It used to be some of us would crawl under a table 3-4 years ago when TNC mentioned it wanted to solve gulf hypoxia. That’s gone down.” But, “We are in a dangerous moment presently: speed is picking up and I’m feeling worried about losing team connections.”

Hypoxic Zone Map

With all the enthusiasm from the new spirit of collaboration, we “don’t yet see much positive conservation change,” adds Tabas. “Our work with and through the the North American Ag program is at a high point. We are successfully building external partnerships with the agriculture industry. The Atchafalaya land acquisition was achieved.” But sooner or later skeptics will point to the paucity of measurable conservation outcomes, especially against the backdrop of TNC’s traditional emphasis on just such results. Of course all this starts with the lofty ultimate goal of a 20% reduction of hypoxic zone. Murray Allen says, “I think the main skeptics will want to know whether TNC is on track to reduce it. Many measurable conservation outcomes are coming into play, but will they add up?”

Plus, there are lots of reasons to question just how far the collaboration spirit has penetrated within the organization. In a recent conversation about the inevitable push back of the “organization immune system,” it was acknowledged that “power issues” still exist and that “it is hard to describe the changes in working together to people ‘who cannot hear it.’” Reuter characterized the present state as there being “two cultures – the traditional culture of strong hierarchical leadership and the new culture of shared leadership – trying to figure out how to co-exist.” Glendening added, “I worry about new people wanting to put their stamp on it.” Knowing that what brought them to this point has been a slow, dedicated process of deeper listening, building trust and learning to think and work differently together, she asks, “What happens when something else gets sexy?”